Something went Wrong

Try entering your email again or contact us at support@qfi.org

Try entering your email again or contact us at support@qfi.org

You’ll receive an email with a confirmation link soon.

Oct 5, 2024

By Dr. Giovanna Fassetta

According to Scottish Government 2024 pupil census, Arabic is the fourth main home language (after English, Polish and Urdu) spoken by pupils who attend Scottish schools. To express welcome and to convey ‘linguistic hospitality’ to Arabic speaking ‘New Scots’ – i.e. people who arrive in Scotland seeking refuge – the Welcoming Languages (WLs) project developed a bespoke, beginner Arabic language course to be taught to school staff in Scottish primary schools.

Since 2022, the WLs project is led by a team based at the School of Education of the University of Glasgow (UK) in collaboration with a team at the Arabic Center of the Islamic University of Gaza (Palestine). As part of two iterations of the WLs project (funded by the AHRC and the University of Glasgow), 30 staff have taken the Arabic language course to date, 19 in Glasgow and 11 in the Edinburgh and Lothian areas.

Two students learn together in an Arabic language classroom.

An Arabic Beginner Course for School Staff

The WLs Arabic language course for beginners was built on the linguistic needs identified by primary school staff and Arabic speaking children and their parents/carers. The project’s needs analysis stage highlighted the language that staff, children and parents thought was crucial within the context of primary education. We grouped the suggestions into three main themes:

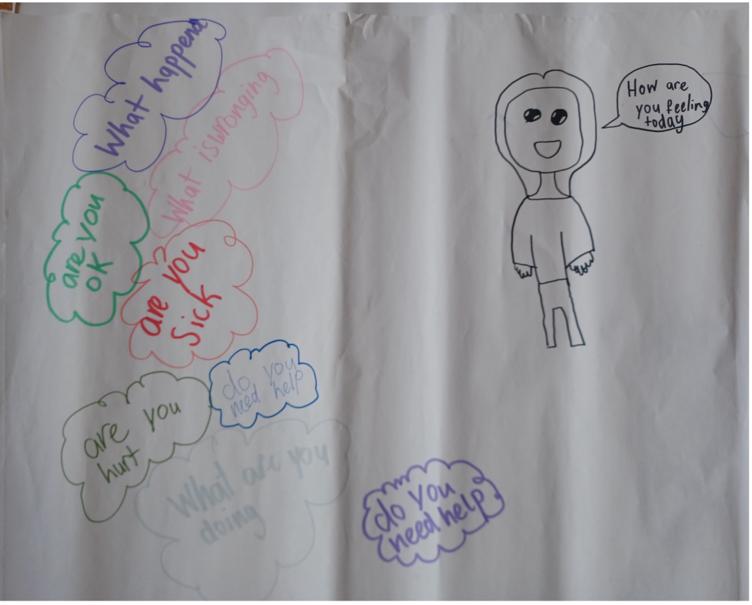

It is important to note that both ‘language for hospitality’ and ‘language for wellbeing’ address the crucial need of establishing interpersonal connections, showing empathy, and ensuring communication in case of illness or distress. This was a need that emerged from all interviews/focus groups carried out at the needs analysis stage. For example, one of the staff told us: “I need to know what to say when children are crying”; and, when asked what staff in their school should learn to say in Arabic, a group of Arabic speaking pupils designed this poster:

Poster on the language that staff should learn by a group of Arabic speaking children.

Course Impact: What the Pilot Reveals

Findings from the first run of the WLs project show that teaching Arabic to school staff can have both a practical and symbolic impact on all involved. In addition to using Arabic for very basic communication with pupils and parents/carers, Arabic-learning by staff clearly demonstrated to Arabic speaking children and their families their resolve to welcome them and share some of the linguistic effort, rather than expecting the children and families to do all the work.

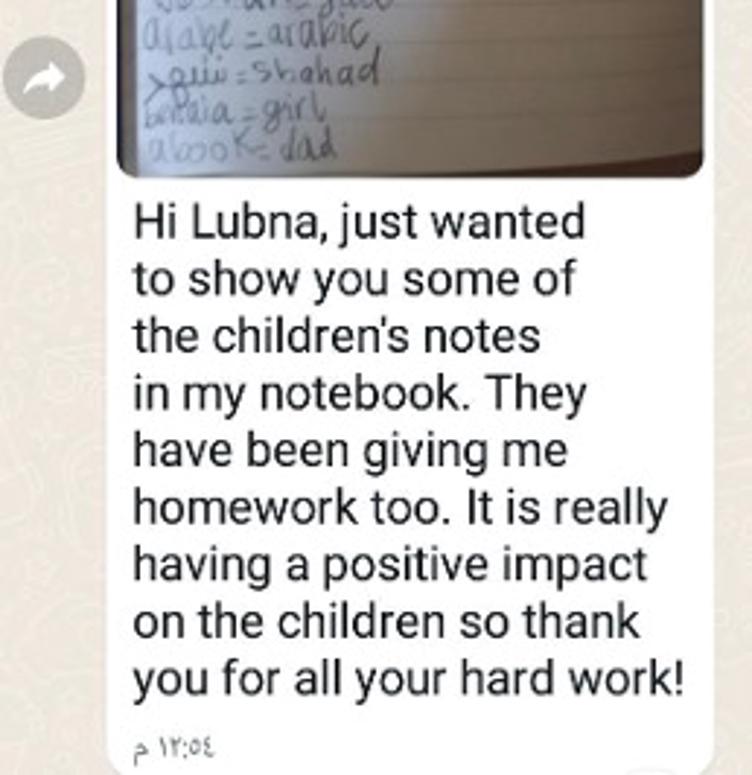

Arabic-speaking children and families also saw their language valued as worthy to be learnt by professionals in their schools. Several young people took on the position of the expert rather than being seen primarily as needing to improve their English language proficiency, as this screenshot by one of the Arabic learning staff (a class teacher) exemplifies:

Screenshot from a WhatsApp conversation between an Arabic learning member of staff in Scotland and their Arabic teacher in Gaza (screenshot shared with consent).

For some of the primary staff, learning Arabic also meant gaining a better understanding of the demands that are put on New Scots pupils and their families and the challenges that they may be experiencing while learning (in) a new language as well as adapting to an entirely new life. This realisation also had a positive impact on their teaching approach and several teachers used the Arabic they were learning for mini-Arabic lessons in their classes.

The WLs project had an impact on all learners in the participating schools, regardless of their linguistic backgrounds, as it demonstrated the value of home languages and fostered new understanding between students and educators of all backgrounds.

Dr. Fassetta is Senior Lecturer in Social Inclusion at the University of Glasgow (UofG, School of Education). Giovanna's research focuses on the inclusion in education of children and young people from migrant and refugee backgrounds, with a particular emphasis on the role of languages in the process of inclusion. Giovanna has led several projects in collaboration with the Arabic Center at the Islamic University of Gaza, the latest of which is the AHRC-funded Welcoming Languages project. In this project, the international research team delivered a beginner, bespoke Arabic language course to staff in Scottish primary schools, thus assisting them in offering ‘linguistic hospitality’ to Arabic speaking pupils and their families. Giovanna is Co-I in the Learning for Informal and Non-formal Educators project, which supported non-formal teachers in four schools in refugee camps in Lebanon as well as refugee English language teachers in Jordan. She is also currently Co-I in the British Council-funded LINEs for Palestine project (Language for Resilience grants). As part of this project, University of Glasgow academics volunteer support to English and Education graduates and ESOL teachers in Palestine, through online workshops and one-to-one mentoring.